SUMMARY

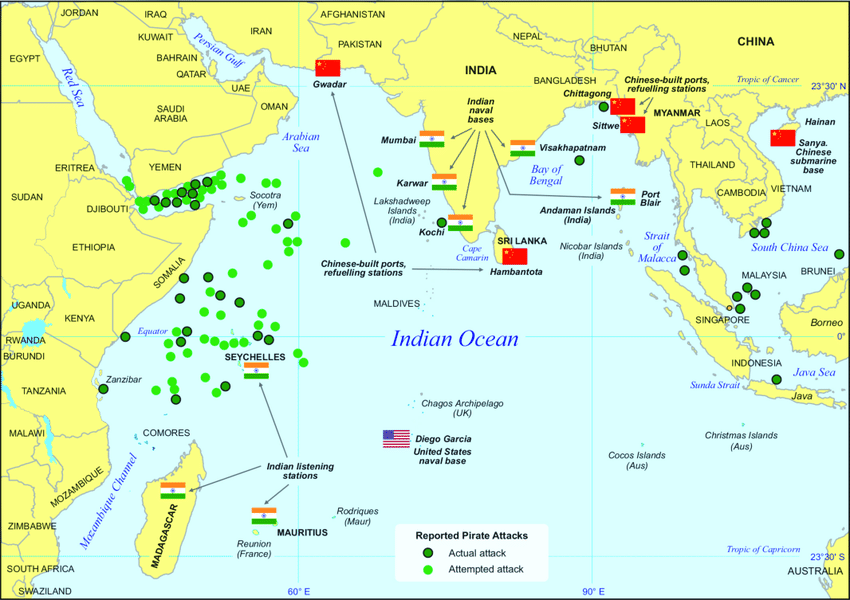

China is racing ahead with its strategic moves in the Indo-Pacific region while the world is preoccupied with Corona health crisis. The past six months saw China maneuvering to strengthen its claims over disputed territories of the South China Sea and operationalize its capabilities for “far sea” warfare. While the American deterrence in the South China Sea is still effective in preventing Chinese adventures, Beijing does not seem to feel constrained in the IOR by any such fears with the US already expressing its intentions to withdraw or reduce its forces from much of the region. While India has acted fast to strengthen its naval capabilities, it still faces severe limitations in thwarting Chinese threats. Some of the suggestions offered to build effective defenses include public-private partnerships in reorganizing fishermen networks as first line of defense and using the Andaman and Lakshadweep Islands as transshipment zones for goods from and to various ports of India and its neighbours which will enhance not only their economic potential but India’s power projection.

*****

by Prasad Nallapati

While the world is pre-occupied with containing the Covid-19 pandemic and hence putting off their military plans, China seems to be racing ahead unabated with their strategic moves. The latest in a series of actions taken by Beijing are border scuffles with Indian forces in eastern Ladakh and Sikkim. The Chinese have been active past few weeks expanding their military infrastructure along these contested border areas.

China keeps indulging in such activities to keep India reminded of their claims over the disputed areas. The two countries, however, have an effective border management mechanism to resolve such skirmishes. They were thus promptly resolved at the level of local formation commanders.

But, is India similarly well prepared to deter China’s more ambitious military maneuvers in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR)? Indian Navy says “yes”, but it is not very convincing.

China’s Maritime Maneuvers – UUVs

A dozen Chinese underwater drones, Haiyi or Sea Wing, were discovered in the eastern Indian Ocean in March this year prompting Indian Navy to issue a statement on April 14 asserting that its naval assets remain “mission-ready and prepared for immediate deployment should the need arise.” According to Chinese government sources, these “Unmanned Undersea Vehicles (UUVs) were launched in mid-December last year and recovered in February after making more than 3,400 observations, which were transmitted in real time to their mother ship, the 4,900-ton survey vessel Xiangyanghong-06. They have thus completed their mission undetected.

The UUVs are used, among other things, to track adversary submarines, detect underwater bombs, deploy surveillance equipment and monitor undersea infrastructure. They are relatively cheaper and hence easily expendable, if necessary.

China has now been deploying these types underwater drones en masse in the Indian Ocean. A sea drone, with Chinese markings, was caught in May last year by Indonesian fishermen off the Riau Islands, along the Straits of Malacca.

Research Vessels

China has similarly been deploying marine research vessels in the continental shelves of other countries of the Indo-Pacific region ostensibly for scientific research and surveys without seeking their prior permission. In one such encounter, Chinese research vessel, the Shivan-1, was chased out of India’s EEZ off the Andaman Islands in September 2019. Similar incidents were reported off the disputed waters of Vietnam and the Philippines. At any given point of time, four to five Chinese research vessels are mapping different parts of the Indian ocean. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), to which China is a signatory, requires nations to seek permission at least six months in advance for marine scientific research in the territorial waters of other countries.

Illegal Fishing

Chinese fishermen are known to be operating far from its own shores in distant waters of other countries, often illegally. Six Chinese fishing trawlers were impounded on April 2 by South African authorities and made them to pay fines for entering their waters without the required permission. The trawlers were detected entering the South African Exclusive Economic Zone off the Northern Cape coast after they were first ordered out of the Namibian waters. In a similar previous transgression by three Chinese fishing vessels, fines totaling US $ 70,000 were charged after more than 600 tons of squid was found aboard the ships. Such incidents of transgression by Chinese trawlers were reported off the coasts of east African countries and even Iran.

These large fishing vessels are always backed by a network of transport ships as the fish catch was regularly transferred mid-sea to these ships and transported back home while the mother ships continue to operate in these distant waters for longer durations. They were thus able to deceive and deflect punitive actions from local maritime regulatory authorities as they could not find any catch of fish. Many of these ships are possibly under control of the Chinese maritime militia and may be carrying transponders to relay real time intelligence.

Expansion of Military Bases and Ports in IOR

China has been building or expanding ports in several countries around the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, which connects to the Atlantic Ocean. They are integrated into its strategic “Maritime Silk Road” plan, called the Border and Road Initiative (BRI). Some of them serve as naval bases while others are expected to provide docking facilities in time of need.

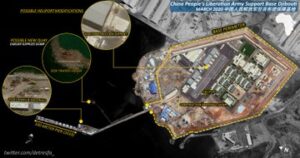

Recent satellite images show completion of a new large pier or a quay as part of the expansion of the Chinese naval base in Djibouti, significantly increasing its capacity. According to H.I. Sutton, an imagery expert, “Major work on a 1,120-foot pier appears to have been finished late last year. This is just long enough to accommodate China’s new aircraft carriers, assault carriers or other large warships. It could easily accommodate four of China’s nuclear-powered attack submarines if required. But it is still relatively limited so it seems natural that China would look to increase the piers.” Djibouti is a strategic port on the mouth of the Red Sea with easy access to the Arabian Sea, Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean.

As reports of the completion of the new pier coming in, the Chinese Ministry of National Defense (MND) announced on April 29 the deployment of the 690 personnel-strong 35th Task Force of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) to the Gulf of Aden to carry out anti-piracy patrols in the Indian Ocean. The task force, comprising at least two dozen naval helicopters and refueling ship, the Chaohu, will also support vessels off the coast of Somalia, despite the fact that there has been no incident of piracy in the area for past several years.

Notwithstanding the Chinese desire to take control of the ports it is building in key locations, it has limitations of using its “debt-trap” as a tool for military expansion. Naval access is the prime concern of China in extending its infrastructure loans to develop ports in countries like Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Djibouti, etc. However, it does not work always. Sri Lanka has denied access to its Hambantota port for Chinese submarine visits since 2017 when a revised lease deal was signed to adjust debt repayments. Myanmar and Bangladesh are also unlikely to grant such facilities under prevailing conditions. Djibouti and Pakistan belong to a different category.

Chinese Military Maneuvers in South China Sea

Early in April, the Chinese survey vessel Haiyang Dizhi 8, accompanied by several coast guard and maritime militia vessels, encroached into Malaysia’s exclusive economic zone to protest its ongoing energy exploration activities. These maneuvers started late last year and continued into 2020. China has also been carrying out such aggressive operations in the disputed waters of Indonesia, Vietnam and Japan. Tensions between Indonesia and Vietnam over fishing rights are being exploited by Beijing to drive a wedge among the ASEAN members. China has further angered Vietnam by creating on April 19 two administrative districts in South China Sea; Nansha District, which is based at Fiery Cross Reef, an artificial island built by China, to oversee Spratly Islands and Xisha District, based on Woody Island, to oversee the Paracel Islands.

PLAN’s Preparations for Offensive Operations in Indo-Pacific

Simultaneously, the PLAN has been preparing for “far seas” warfare since the past four years. The “ZHANLAN” annual “far seas” training series was launched in May 2016, with its each iteration growing in complexity. This year’s (17 Jan-25 Feb) training program was significant as its focus was on combat support, rather than kinetic operations. Roderick Lee of the Jamestown Foundation stated, “The key takeaway from this training event is that the PLAN is developing the proficiencies to sustain limited offensive strikes against US forces – perhaps as far out as Hawaii.” The PLAN is close to being able to execute offensive naval operations outside of the first island chain (and perhaps beyond the second island chain) in a wartime environment.

A report of the US Department of Defence acknowledged, “The PLA is developing power projection capabilities and concepts of operation in order to conduct offensive operations within the second island chain, in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, and in some cases, globally.” The PLAN, Lee argues, may be closer to operationalizing those capabilities.

CONCLUSIONS

These Chinese maritime military maneuvers during the last six months coincided with Corona-virus pandemic prompting many experts to conclude that Beijing is taking advantage of the world’s pre-occupation with the viral crisis to accelerate its own strategic agenda. However, these Chinese maneuvers in the IOR and South China Sea reflect continuity of its strategic moves and not opportunism due to Corona epidemic, according to Taylor Fravel, a noted China expert.

Retired PLA Air Force Maj. Gen. Qiao Liang, now a professor at the PLA National Defense University, has also rejected the notion of Beijing taking advantage of the pandemic to take Taiwan by force. In a statement on May 4, he admitted that the pandemic crisis creates a short tactical window for China, which is, however, not big enough to solve the strategic dilemma it will face in the future. “The Taiwan issue is actually a key problem between China and the US, even though we have insisted it is China’s domestic issue. In other words, the Taiwan issue cannot be completely resolved unless the rivalry between Beijing and Washington is resolved.”

There is thus a functional American deterrence in the South China Sea, at least in the short term, against China making any military adventures there. But there is yet no such effective deterrence in the Indian Ocean Region. With changing geo-political interests, the US has made its intentions clear to withdraw its military deployments from the Middle East, Africa and Afghanistan and reposition them elsewhere in East Asia to deter challenges from China. Sri Lanka has refused to enter into a Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) with the US thus denying it any access to its ports.

China thus finds an opening to fill in the Indian Ocean Region. Its military bases in Djibouti and Pakistan and other port facilities in the region provide China vast advantages. The recent Chinese military maneuvers in the Indian Ocean are thus part of its larger strategy to extend its reach befitting its superpower-dream and constrain Indian maneuverability.

India has, understandably, moved fast to create new technical capabilities to monitor the IOR, such as the Fusion Centre (IFC-IOR) and other monitoring outlets in Mauritius, Seychelles, Maldives, etc. Its defense cooperation agreements with the US, France, Japan and Australia provide India access to their military equipment, technology and naval bases in the region. Indian armed forces are being restructured into more effective Joint/Theatre Commands.

However, there are still severe limitations in realizing the power that India can wield in the Indian Ocean which include inter-service rivalries and lack of public-private partnerships. I will focus more on the latter here as that has been the key for the maritime military successes of both the US and China.

India has not just neglected but outright destroyed its vast coastline assets, i.e., the Fishermen. The Maritime Agreements of 1974 and 1976 with Sri Lanka have effectively taken away traditional fishing rights of Tamil Nadu fishermen in and around Kachchativu island. The maritime territorial demarcations with Bangladesh and Pakistan have also severely curtailed the reach of the Indian fishermen, who often get arrested and their boats confiscated as they drift inadvertently through the invisible demarcation lines.

The Indian government paid only scant attention to their plight and the promises of providing financial and other assistance for alternative fishing arrangements like deep sea fishing have never been followed up. The result is that the first line of defense is totally collapsed. It is no wonder that a handful of terrorists sailed in a fishing boat all the way from Pakistan to wreak havoc on Mumbai city in 2008.

In contrast, China has a huge fishing fleet and the PLA has created out of it a massive network of maritime military militia. They lead many of initial expeditions into disputed territorial waters of South China Sea, closely supported from behind by its coast guard/naval forces. The fishing trawlers operate far into distant waters of the Indian Ocean as well doubling as spying apparatus. China uses its fishermen to comb the near seas and find any “spy drones” and other activity for which they are richly rewarded. The fishermen recovered last year seven such UUVs, deployed by either the US or its allies, and nine a year before off the coast of Jiangsu province facing Japan and South Korea. The rewards were huge ranging upto US $ 70,000 and were presented during well publicized public functions. China is also now the largest container ship-owning nation adding more arsenal to its intelligence gathering.

It is time for India also to reorganize its vast network of fishermen into large public-private partnerships and coopt them in strengthening its first wall of defense. As marine fishing declined, inland fishing gained corporate-level investments which now account for major fish exports. These big businesses can be lured into deep-sea fishing with liberal incentives. That will enrich the coastal communities that are currently living deep in poverty.

It may be worthwhile to explore using the Andaman Islands in the East and Lakshadweep Islands in the West for transshipment of goods from and to Indian ports as well as that of its neighbours. Small cargo ships plying between these islands and various ports in the region can also serve as “eyes and ears” of the Indian Navy. It not only enhances economic potential of the islands and other port cities but also India’s power projection.

(Prasad Nallapati is President of the Hyderabad-based think-tank, the Centre for Asia-Africa Policy Research and former Additional Secretary to Govt of India)