By Nallapati A. Prasad

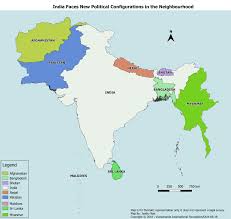

The news of the visit of the Chinese oceanic Survey and Research ship, Yuan Wang 5, to the Beijing-controlled Sri Lankan port of Hambantota from August 11 to 17 raised security concerns in India. The stated purpose of the visit was for replenishment, and it is expected to conduct satellite control and research tracking in north-western part of the Indian Ocean. While we do not know what else it may be doing during its stay there, an overview of the recent activities of China’s Survey ships in the region provide a clue to the mystery.

Chinese research vessels have regularly been seen conducting oceanic surveys in Sri Lankan waters and eastern Indian Ocean region. There have been 12 such declared visits to the Sri Lankan waters since February 2014 and many more may have not come to the notice of the Island authorities. The last such known visit was during October-November 2020 when two Chinese vessels conducted surveys in Sri Lankan waters for over a month.

While civilian oceanic survey is permitted in high seas, prior permission is required for such activity in territorial waters of other countries, for which a request is to be submitted six months in advance. Sri Lankan Navy had earlier admitted that no such permission was ever taken and their requests to board the vessels to check their activity in their territorial waters were snubbed.

The Indian Navy had spotted and expelled a Chinese research vessel operating without permission in its territorial waters off the coast of Port Blair in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in September 2019. The Shi Yan-1 ship (Experiment 1), which is owned by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, was apparently carrying out unlawful activity. Commissioned in 2009, Shi Yan 1 is one of the most advanced scientific research ships capable of carrying up to 45 scientists and is fitted with more than a dozen laboratories.

Shi Yan-1

The then Naval Chief, Admiral Karambir Singh, had stated that at any time, seven or eight Chinese ships could be found in the region. That means that several of these vessels go undetected.

It is not just the subcontinental waters, the Chinese survey vessels enter the exclusive economic zones (EEZ) of Southeast Asian countries at will on an almost daily basis.

Survey Ships in Southeast Asian waters

In January 2021, two Chinese vessels, Xiang Yang Hong 01 (XYH 01) and Xiang Yang Hong 03 (XYH 03), had carried out extensive research along the underwater mountain range, the Ninetyeast Ridge, in eastern Indian Ocean, south of Andaman and Nicobar Islands. XYH 01 transited the Malacca Strait and operated further north of its sister ship, while the XYH 03 took the Sunda Strait, off the Indonesian islands of Java and Sumatra, and surveyed further south.

Ninety East Ridge – Courtesy: www.en.wikipedia.org

What was intriguing about their activity was that the XYH 03 “went dark” while in the Indonesian waters, which means shutting down its transponders to hide its position. This was the time when several Chinese underwater drones turned up in Indonesian “sovereign” waters.

Another ship, XYH 06, had deployed at least 12 drones in Indonesian waters in late 2019. It also “went dark” for four days while crossing Indonesian EEZ giving enough time to deploy the gliders. “The 12 underwater gliders carried out cooperative observation in a designated sea area. Together they travelled more than 12,000 km and conducted more than 3,400 profiling observations, obtaining a large number of hydrological data…,” the Chinese Academy of Sciences said in March 2020.

The ship, Haiyang Dizhi 8, was noticed operating in Malaysian EEZ in April 2020 near an oil exploration site. It was seen towing away a sensor array, escorted by 8 other militia vessels, while surveying a swath of Malaysian continental shelf.

In all, seventeen Chinese vessels were recorded operating in another country’s EEZ or in undefined international boundaries in the year 2020, and more than 10 of them were reportedly involved in suspicious activities.

Research Activity that helps Submarine warfare

H.I. Sutton, an analyst of satellite imageries, stated that the survey ships may not have an overtly military mission, but the data gathered will likely be of particular interest to the Peoples’ Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). Ocean survey data is useful to both military and civilian interests. China has been systematically surveying vast swathes of the Indian Ocean. Four of the Xiang Yang Hong (“Facing the Red Sun”) research ships, XYH 1, 3, 6 and 19, have been very active in the region in recent years.

“They are paying particular interest to surveying the Ninetyeast Ridge, an underwater mountain range that cuts down through the Eastern Indian Ocean from north to south. The range is particularly relevant for submarine operations. If Chinese submarines are going to increase their activity in the Indian Ocean, these maps may aid the sub’s survivability,” he said.

A report of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative of Washington’s Center for Strategic and International Studies published last year further amplify this point. “Understanding the bathymetry in these areas is critical if Chinese submarines hope to effectively operate beyond the ‘first island chain’ surrounding China’s near waters,” the report said.

In an article published on NavalNews, Sutton wrote that some of the survey activities, nearer to Indonesia and the Andaman and Nicobar islands, could relate to finding the US Navy’s reputed ‘fish hook’ sensor networks. These are designed to track Chinese submarines entering the Indian Ocean.

Gliders support underwater observation network – Underwater Great Wall

The underwater gliders recovered from the Indonesian waters were of the Sea Wing (Haiyi) type that could act as communication and data-relay nodes to help rapidly transmit information useful for detecting and tracking foreign submarines.

China’s Sea Wing underwater drone. Courtesy: www.navaldrones.com

The Sea Wing drones, which may have also been deployed elsewhere in the Indian Ocean, are said to be used purely for oceanographic research, taking sonar soundings of the ocean floor and measuring the strength and direction of the currents, water temperatures, salinity, turbidity and oxygen levels. But the same data is useful in future naval operations. The research into propagation of sound underwater paints a picture of the acoustic and thermal environment, allowing submarines to hide under layers of thermocline to avoid sonar detection from surface ships. These drones may also be pre-cursers to a new generation of armed UUVs that could launch missiles against enemy vessels.

Malcolm Davis, an analyst with the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, and other naval experts believe that these underwater gliders need to be further examined as they could fit into the Chinese scheme of building a network of sensors and platforms that will give the PLAN a better “situational awareness” of the movement of enemy ships in the Indian Ocean region.

China Shipbuilding Industry Group had inadvertently exhibited in June 2016 an ambitious program called, “Undersea Observation Network”, which the Jane’s Defense Weekly dubbed as the “Underwater Great Wall.” The US National Interest website stated that China’s ambition to build an underwater observation system will apply to all oceans that touch China’s national interests, including “offshore, deep sea, remote islands, and strategic channels.”

The underwater sound monitoring system plays a key role similar to the air defense radar warning network in antisubmarine warfare, but only changes the radar to sonar. The Chinese government has revealed the existence of two underwater sensors situated between the island of Guam and the South China Sea. Though officially for scientific research, the undersea listening devices are likely doing double duty, monitoring the movements of American and other foreign submarines and potentially intercepting their communications. The state-run Chinese Academy of Sciences only disclosed the pair of acoustic sensors earlier in January 2018 but had been operating them since 2016.

Role of Western Universities in aiding China’s underwater research

Western universities in Europe and the US had proven to be willing partners in joint research that would facilitate building the Underwater Great Wall. Dutch scientists of the TU Delft collaborated with Chinese military academics since 2016 to develop a type of underwater GPS. They developed underwater sensors that emit acoustic signals that have military application. The entire funding came from the National University of Defence Technology (NUDT), which is part of the China’s Peoples’ Liberation Army (PLA). Many of these and other studies with Chinese military academics concern underwater drones (gliders), underwater sensors, and buoys with sensors, or concern studies into AI and mathematical models that can be applied to underwater drones and sensors.

Monitoring Submarine cable nodes

The data provided by the Survey vessels would be useful for Beijing’s Digital Silk Road project which involves not only creating telecom infrastructure but also acquiring capabilities to collect data worldwide through interception of internet cable systems, including submarine networks. As seen above, the survey ships could deploy underwater sensors to monitor submarine cable networks.

There are five cable landing stations in Sri Lanka linking submarine-cable connections, such as Sri Lanka-Maldives link, Tuticorin-Colombo link and the South East Asia-Middle East-Western Europe (SEA-ME-WE ) 3 and 4. Huawei, a Chinese telecom company with close links to its PLA, built a 700-kilometre submarine cable providing high speed communications to Mauritius’ second-largest island, Rodrigues. The MARS undersea cable, one of more than a dozen laid by Huawei in Africa, also lands at Baie-du-Jacotet landing facility in Mauritius, which recently attracted a controversy as Indian experts visited the facility reportedly to check China’s backdoor interception.

Conclusion

While we do not know the real purpose of the Yuan Wang 5’s scheduled visit to the Hambantota port next week, the above review gives an overview of the capabilities of these research and survey ships, which have both civilian and military objectives. Their survey data benefits PLAN’s submarine operations. The underwater drones deployed by these ships could be part of the “Underwater Monitoring Network” that was already deployed in South China Sea and now being laid in the Indian Ocean region. Such tools would give an edge to PLAN over enemy naval operations. Further, they could also play a role in monitoring submarine communication networks. This all fits into China’s larger strategy to be global maritime power by the year 2030, on par with the US Navy’s capabilities.

(Nallapati A. Prasad is President of the Hyderabad-based think tank, “Deccan Council for Strategic Initiatives”, and former Additional Secretary to the Govt of India)