Saudi Arabia, under the youthful Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, stripped off the powers of the religious police in 2016, but the Islamic Republic has no such appetite for reform

by Prasad Nallapati

The death of a 22-year-old Kurdish girl in custody of Iranian `morality police’ on September 16 has sparked countrywide anti-government protests and civil unrest over the past two weeks. Mahsa Amini’s offense was reportedly wearing a loose hijab (head cover). The protests were initially led by women but soon became a national call with people from middle and lower classes joining them demanding wider civil liberties.

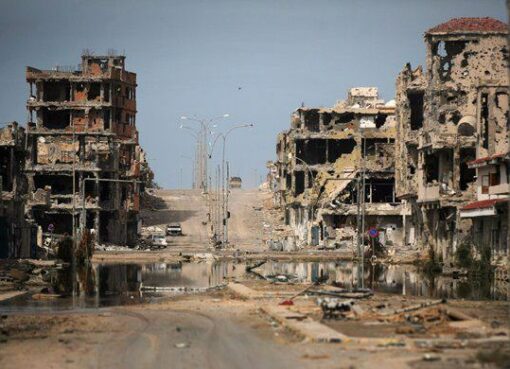

The response of the regime to the riots was quite brutal. At least 76 people were killed in the clashes, according to Human Rights groups. Severe internet restrictions were imposed while social digital platforms made inaccessible. Thousands were detained including journalists and TV celebrities. Although demonstrations are continuing undeterred, with women openly defying hijab, they seem to be slowing down owing to the harsh measures adopted by police forces.

The hijab issue per se is not the major reason for such heavy response from the government. There are other factors at work that are more challenging from the regime’s perspective, which are only getting exacerbated due to lack of progress in negotiations for reviving the nuclear accord, JCPOA, and lifting of US sanctions.

The Iranian regime, comprising dual power centres of Shia clergy and Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), is not a monolithic conservative body as many outside the country believe. Their leadership range from hardliners to liberals to reformists. They are modern in approach in some aspects like allowing women access to higher education, discoursing polygamy, and enforcing population control measures. But it’s a different ball game when it comes to personal and political freedoms.

Notwithstanding the divisions within the two power centres, they act in unison in protecting their political turf. Hence, any unified opposition activity from outside their ranks is seen as a challenge to their power and doggedly fought to crush it even before it evolves into a threat.

Regime sees `Underprivileged and Middle-Class Unity’ a Threat

According to Ali Alfoneh, author and senior fellow at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, the worst prospect, from the regime’s perspective, is “the underprivileged joining the middle class, since they no longer as socially conservative as in the past and because of their economic grievances, which they share with the middle class.” The underprivileged was the backbone of the 1979 Islamic revolution launched by late Ayatollah Khomeini.

“The regime has hitherto managed to play the middle class and the underprivileged against each other and suppress both. Should the middle class and the underprivileged join forces in the future, they will constitute a formidable challenge to the regime,” says Alfoneh.

Fears of `Regime Change’

The clerics also see the protests as part of `regime change’ policy of foreign powers inimical to the regime, such as the US and Israel. Spiritual Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei said (October 2), “This rioting was planned. I say clearly that these riots and insecurities were designed by America and the Zionist regime, and their employees.” President Ebrahim Raisi stated (September 30), “We should not allow the enemy to weaken our national unity.”

Ayatollah Ahmad Khatami, Tehran Friday prayer leader, in his sermon on September 23 identified two sections of protesters, one to be treated lightly and the other without mercy: “…there were two types of people, one group of inexperienced youth, who were misled by foreign media broadcasts, and second group is leaders of the unrest, who are guided and funded by foreigners.”

The US Treasury Department measures to expand internet access to help Iranian protesters appear to give credence to the allegations by the Iranian authorities. Deputy Treasury Secretary Wally Adeyemo said last week, “The US is redoubling its support for the free flow of information to help the Iranian people be better equipped to counter the government’s efforts to surveil and censor them.”

Kurdish Mobilization

Fears of a Kurdish mobilization may also be troubling the regime as the victim of the hijab controversy, Mahsa Amini, is a Kurd. Tabnak News, close to former IRGC Commander Mohsen Rezaei, reporting (September 24) on Iranian attacks on Kurdish areas across the border, said, “As heavily armed forces of the terrorist Komala,” Kurdish armed opposition group, “relocated to the border towns to instigate unrest and rebellion in Iran, the ground forces of the IRGC targeted positions of the group in the Iraqi Kurdistan region.”

Conclusions

The intensity of the Iranian response to the protests may, therefore, be part of measures to protect the regime. Hence, the demands of the protesters to rein in `morality police’ and make the hijab voluntary are unlikely to be met.

In early Islam, there was no `morality police’, which came much later as clergy and ruling class joined hands to establish their unequivocal control over people. It gained new prominence in Saudi Arabia as the House of Saud and Wahabis made a pact in early 20th century to create an `exemplary’ Muslim state. It came much later in Iran after the Islamic revolution when Ayatollah Khomeini sought to rein in the citizens after a bout of secularism under the Shahs.

Saudi Arabia, under the youthful Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, stripped off the powers of the religious police in 2016, but the Islamic Republic has no such appetite for reform.

(The writer, a former Additional Secretary to Government of India, heads the Deccan Council for Strategic Initiatives, a think-tank based in Hyderabad)