However the war ends, there would be no winners. Ukraine would end up a broken state indebted to Western countries, while Russia’s military reputation grievously hurt, limiting its ability to play a stabilizing role in the region. The long frozen territorial disputes would come back to haunt it. Moscow’s capacity to keep the flock of post-Soviet states together under its leadership might get badly eroded with foreign powers stepping in to reshape the region’s new alignments

by Prasad Nallapati

Russia’s Ukraine military conflict appears to be heading into a long drawn bloody war extending beyond fast-approaching winter. Whatever the outcome when it finally ends, neither side would be a gainer. Both end up broken. The post-Soviet space would see far-reaching changes, none likely to be very pleasant.

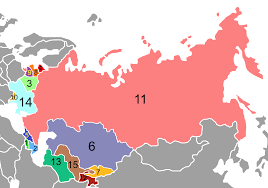

The conversion of the 15 republics of the former Soviet Union into equal number of sovereign states within the existing borders, on the collapse of the USSR three decades ago, was a relatively smooth affair. There were no major population movements across the borders despite people of different nationalities finding themselves in separate countries. Russian speaking enclaves are spread over many border regions of the new republics including Ukraine, protection of which is claimed to be one of the reasons for Russian invasion.

There are similar territorial and political disputes across the region, but Moscow used its clout to successfully keep them under wraps. It maintained regional stability by binding the new republics to Moscow-led institutions like the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), and Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). It doggedly fought to keep outside powers away from its backyard. The US, for instance, tried to instigate `color’ revolutions in these republics to wean them away from Russian influence.

Russia’s Reputation as `honest broker’ Damaged

The military invasion, however, has begun unravelling Russia’s fragile grip over the former Soviet republics. Moscow’s alacrity to use its superior military force in settling its border disputes in its favaour has irretrievably damaged its reputation as an `honest’ broker.

The ceasefire brokered by Russia between Armenia and Azerbaijan, after a bitter war two years ago, broke down as Baku saw it an opportune time, with Moscow preoccupied with Ukraine, to launch a fresh military offensive against Armenian territory to recapture areas claimed by it. Border disputes between the Central Asian Republics of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan flared up into a bloody battle resulting in death of about 100 people before an uneasy peace was put in place.

Foreign Powers Gain Foothold

Turkey’s President Erdogan has forced his way using deft diplomacy, backed by its military muscle. It’s much acclaimed `Bayraktar TB2’ drones led the way to cement strategic partnerships with conflicting sides. It’s strong backing of Azerbaijan forced President Putin accept Turkey in jointly enforcing ceasefire with Armenia. Its drones tipped scales in favour of Kyrgyzstan, forcing Tajikistan also to approach Turkey for similar weapons, and thus creating a new dilemma for Moscow.

Erdogan is in fact nursing much larger ambitions as he attended the last month’s SCO summit personally as an observer where he signaled his country’s interest to become full member of the Organization. In November 2021, Turkey spearheaded the creation of the Organization of Turkic States (OTS) with Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. The expansion of the Turkish drone market in Central Asia could deepen Turkey’s military-strategic influence in Russia’s backyard. Turkmenistan was the first Central Asian republic to acquire the TB2 drones in December 2020. Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan are now eying to acquire them. Erdogan also dreams of creating a transport corridor to Central Asia by arranging a reconciliation between Azerbaijan and Armenia.

Other powers too sense an opportunity. With Russia’s unwillingness to come out decisively in favour of its treaty partner, Armenia, Iran has expressed its readiness to intervene on Armenia’s side if its borders are threatened. It is an important trading partner to Armenia and now wants to upgrade it to strategic level. The US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi also flew into Yerevan to express her support for Armenia where she explicitly said that Russia is not a reliable patron.

Russia’s Growing Isolation further pushing it to embrace China

As the Ukraine war grinds on and Western sanctions biting, Russia is facing increased global isolation, which is further pushing Putin deep into Chinese arms. That will give China more leverage to expand its presence in Central Asia, where it has invested over $40 billion.

President Xi Jinping chose his first trip abroad after the Covid-19 pandemic to visit Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, where he attended the SCO summit last month. Xi sought to convert China-Kazakh relations into a permanent comprehensive strategic partnership, while he held out a more promising relationship with Uzbekistan. Mao Ning, spokesperson of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, said the two visits will provide a new blueprint, new goals and new impetus for China’s ties with the two countries.

While other powers are preoccupied with armed conflicts, China is quietly expanding its foot print through its Borer and Road Initiative (BRI) network. Last week, it activated `China-Afghanistan’ corridor, starting from Kashgar in China to Hairatan, in Mazaar-e-Sharif in Afghanistan, traversing through Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. The first trial shipment of two containers departed Kashgar on September 13 and arrived in Hairatan on 23, cutting down the transit time to ten days. The first leg is carried by truck from Kashgar across the border to the Kyrgyz city of Osh, from there containers are loaded on a train to its final destination in Afghanistan.

The second corridor, China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan (CKU) railway line is also in the offing. It is the new southern branch of the BRI and Uzbekistan is set to become the starting point for rail freight traffic to Turkey, and eventually to Europe, especially to Southeast Europe. The timing of two new similar corridors around the same period shows the seriousness of China to quickly seek alternative trade routes as the war in Ukraine has upset its Eurasian rail freight traffic running through Russia.

Conclusion

However the war ends, there would be no winners. Ukraine would end up a broken state indebted to Western countries, while Russia’s military reputation grievously hurt, thus limiting its ability to play a stabilizing role in the region. The long frozen territorial disputes would soon come back to haunt it. Georgia, nursing its wounds, may try to attempt again to retake two Russian breakaway regions, South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Moscow’s capacity to keep the flock of post-Soviet states together under its leadership might get badly eroded with foreign powers stepping in to reshape the region’s alignments.

(The writer, a former Additional Secretary to Government of India, heads the Deccan Council for Strategic Initiatives, a think-tank based in Hyderabad)